Amane Ishii solo exhibition「warp」/Eri Fukami solo exhibition「fictional reality.」

Exhibition information:

https://biscuitgallery.com/warp-fictionalreality/

Foreword

In 2019, I began putting together a research project titled “MIMIC.” In this project, I, together with Yohei Kumano, the main member, am exploring methodologies for description of artists while leaving their individual complexity intact as far as possible, through research of artists in our midst and archives.

Partly because I took up Amane Ishii in the first installment, for this installment, I decided to contribute a text for the solo exhibitions of Ishii and Eri Fukami that are going to be held simultaneously.

While I am well aware that this foreword may be superfluous, I would nevertheless like to set forth my basic perspective. I believe this approach will facilitate understanding of my later comments.

I like the individual skills and techniques of artists. I am keenly interested in thinking about the yardstick distinct to the particular artist and the peculiar “obscurity” they can have precisely because of who they are.

For example, in painted works, the ability to make sharp, clear-cut lines is proof of a high technical capability. However, not all artists aspire to make such lines. Depending on the case, a weak, wavering line may be absolutely necessary for the artist in question.

It may not be just any kind of weakness; it may be with this weak line that the artist moves toward individuality. This is a matter of technical “quality” arising on a level different from that of newness or public appraisal. In addition, first and foremost, this peculiar “obscurity” is definitely not self-complacency, even if it appears to be stereotyped or immature on the surface.

But it is also true that such individual techniques and outlooks on value may not be amenable to translation into the language of others. Alternatively, there may be some sort of need to intentionally avoid any desire to be understood by others.

The wish to examine methodologies for describing the individuality of artists premised on such “obscurity,” as opposed to any emphasized individuality or a constructivist context, is at the foundation of my awareness on the issue.

It is from the perspective of the aforementioned interest that I view the works of Ishii and Fukami in this text.

At the same time, because both of these artists are active on an ongoing basis, I want to avoid drawing any definitive lines in regard to them. In my remarks, I will therefore refrain from any judgments to a certain extent.

biscuit gallery is holding not a two-person show but two simultaneous solo exhibitions. I will consequently write about each separately instead of straining to make connections between their works. Ishii’s works are shown on the first and second floors, and Fukami’s, on the third floor. I will therefore consider Ishii’s works first.

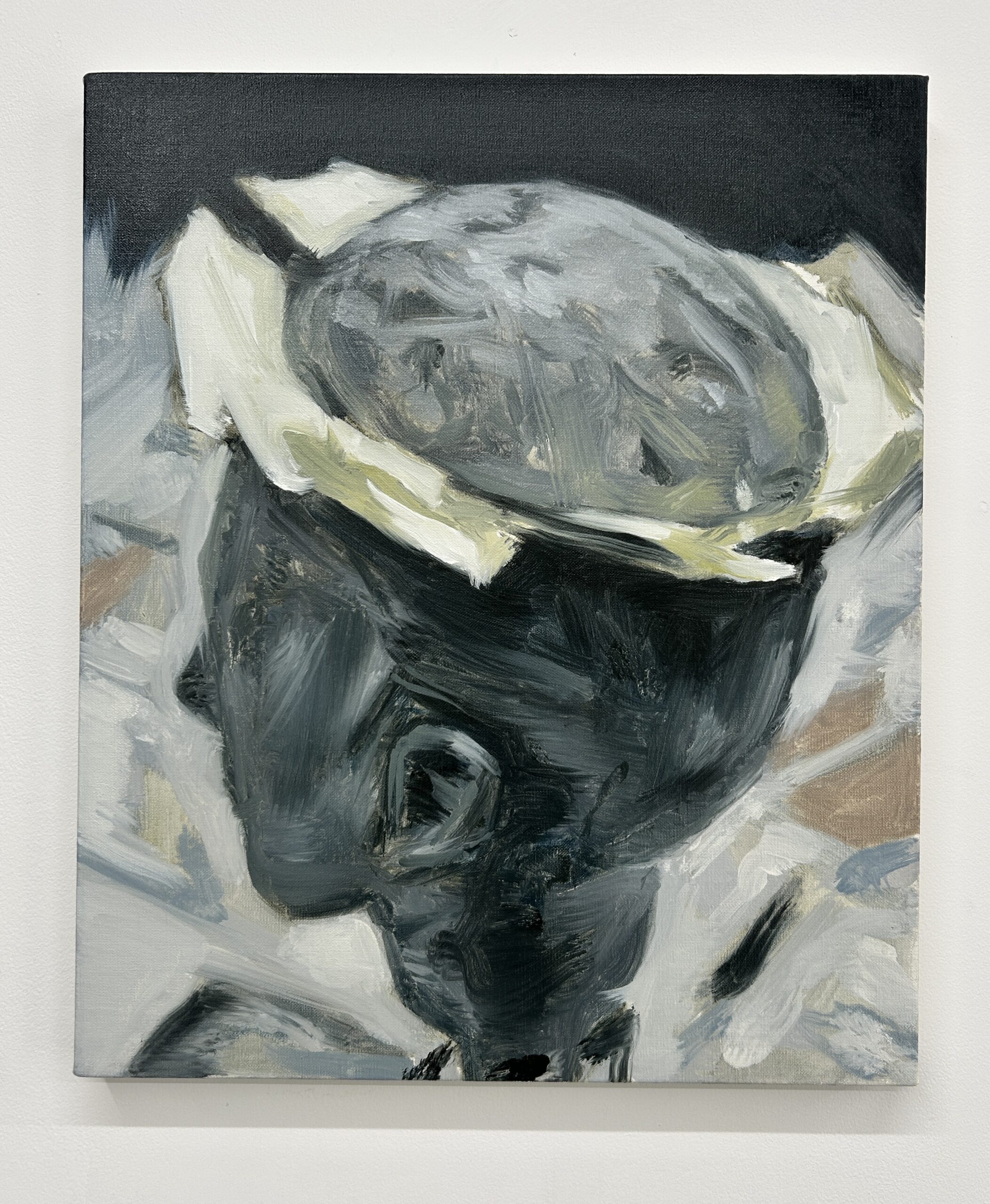

Warp, a solo exhibition of works by Amane Ishii

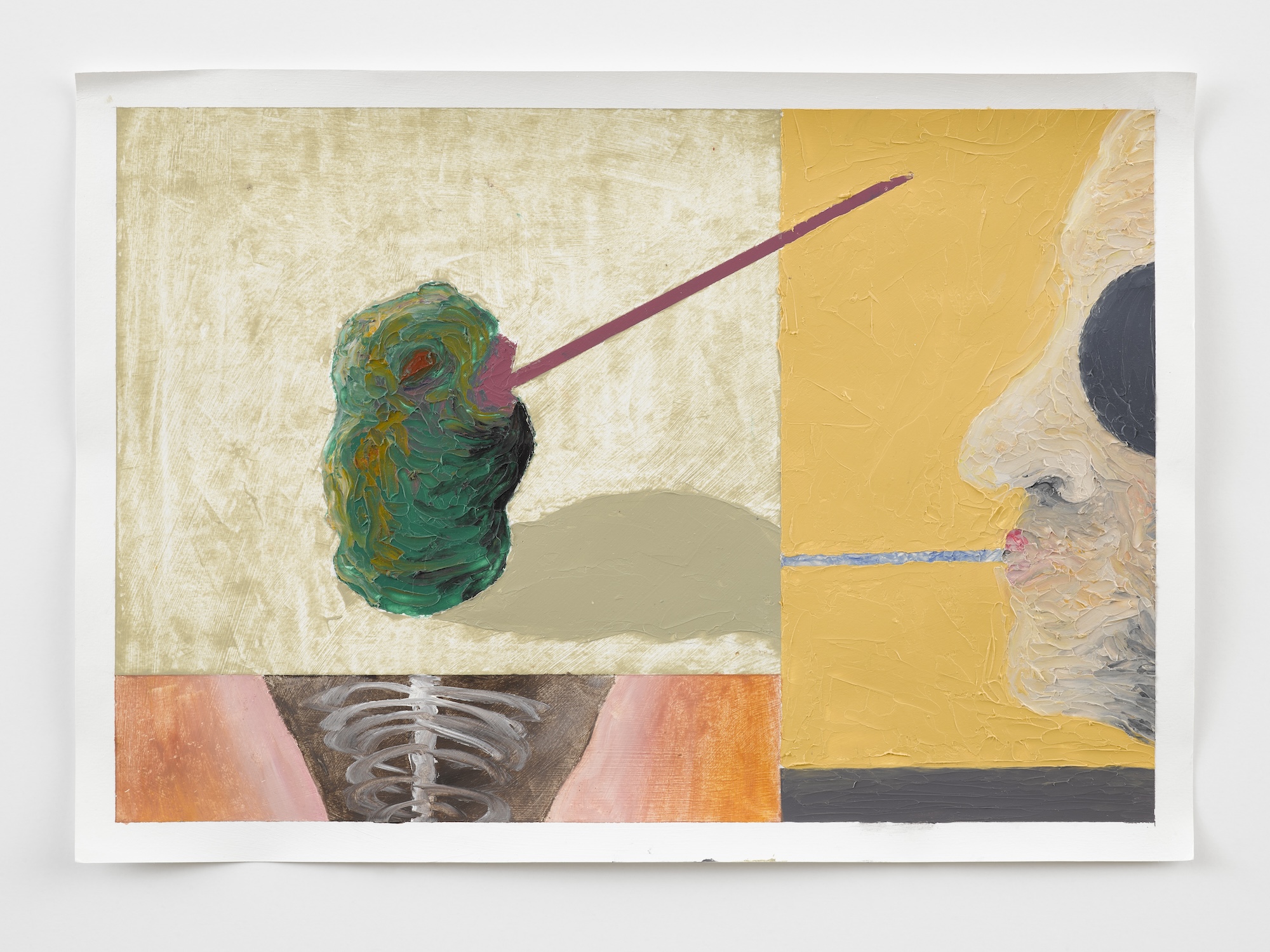

For this exhibition, Ishii said she was going to show portraits. When I went to her studio to take a look, there was a huge canvas of about size 100 containing several portraits in her usual style and girls gazing at them. On the periphery of this work were small portraits that looked as if they had been cut out of larger ones.

So the portraits within the painting were apparently going to be shown in the actual display space, I supposed. I figured this was a natural development for Ishii, because she had repeatedly put motifs appearing in her paintings in paintings within paintings and in other works.

It is difficult to draw an overall picture of Ishii’s works, because their elements are tangled up with each other in the manner of a diffused reflection. But if I were to take one element of her art to ponder in connection with this exhibition, signs and symbols*1 might be a good choice.

Peter Doig, for example, puts boats and grids in different works while changing the style of rendering, size, and motifs applied. By so doing, the images of boats and grids are turned into signs by his own hands. Boats become symbols of Doig.

Similarly, in Ishii’s works as well, the images of girls’ eyes, pointing fingers, goblins, centaurs, and tulips are repeated in various paintings. There is nothing odd about extensive use of favorite icons, but her case is one of deliberate signing through the medium of motifs with a highly referential dimension, such as pictures within pictures and mirrors.

Signs are also deeply intertwined with the change in Ishii’s production attitude in recent years. In Kagami 2 (2019), for example, the tulip takes the form of a child’s scribbling. Just as most people understand that a drawing of a circle with radiant lines around it depicts the sun, the sign in this case has an implication close to those of signposts or ideograms. In Bani kakutasu no nikko fusoku (2021) shown at her solo exhibition in October 2021, however, the plant (albeit not a tulip) is executed in a manner that is even more true to nature than before. In connection with this change, I recalled her comments in an interview in June 2021.

“In the process of using signs and making things flat, you are liable to end up skipping something that you should absolutely do. Things like that could be done later on; only a few years have passed since I started painting. (…) Signs have the aspect of running away, and I think I should be cautious about them.

– From the MIMIC interview with Amane Ishii (omission by the author)

The topic here was whether or not to depict the shadow falling on the painting frame. For Ishii at present, to disregard the appearance of the actual plant and paint on the strength of its atmosphere would probably be a kind of “loafing.” Her comments above suggest that she would not be averse to such abbreviation once she becomes more technically proficient, but she has just begun painting and wants to be better able to paint all sorts of things now.

I really understand this position of hers, and believe that it is having a good influence on her paintings. Furthermore, I think it shows a close linkage with the technical yardstick in her works and the disparity of signs/symbols. Here, I would like to draw an additional line.

Alex Katz came to the fore in the 1950s and is often categorized as a Pop Art artist because of his portraits in the style of illustrations. In an interview with Robert Storr, however, Katz spoke of his interest in producing excellent paintings and reminisced about heading in a direction completely different from Pop Art. He explained this difference from Pop Art from two orientations.

First, Katz cited the difference between signs and symbols.

A sign is like a stop sign, for example, that means “stop!” It has no meaning beyond that.

The sign for the sky is blue. That for grass is green. In Katz’s view, the use of such images clear to anyone, i.e., signs, was characteristic of Pop Art. He said that he, in contrast, was interested in something a little more complex.

That something was symbols. Symbols are not confined to a single meaning, and hover in the background of the portraits drawn by Katz. His first thesis was that he handled symbols, which were much more variable than signs.

Next, Katz cited technical standards. In this connection, he uses the playful expression “big technique,” which is a coinage of his own. The following is a direct quote from the interview.

“The painting performance is something I got interested in. Pollock was pretty good, but when I really got how well Picasso could paint once he got to Girl Before a Mirror (1932). Actually you don’t get a big technique until you’re around 35 or 40, usually, if you’re any good. Picasso’s early paintings were technically, for me, pretty wobbly. Even his great Cubist paintings don’t have a big technique. When he gets into his fifties—when he does Girl Before a Mirror—that’s a big technique. For me, it was just awesome, and that’s what I wanted to do.

“Matisse has a big technique. It took me three or four years to learn how to appreciate paintings. I was in art school, and the teacher said, ‘Take a look at Matisse.’ Well, I fainted; I couldn’t believe anyone could paint that well! That was a big technique.

“So, that’s what my mind was set on—that and the small technique things. They function in terms of invention and they function in terms of fashion and style. There are some terrific Pop paintings, but I had my eye set on something else.”

– From Carter Ratcliffe, Robert Storr, Iwona Blazwick, Alex Katz; Phaidon Press, 2007, pp. 14 – 15.

In a prior interview, Ishii said that she wanted to “throw” her paintings far. This way of expressing her desire to see her paintings remain far into the future strikes me as in keeping with her sensibility.

In it, one catches a subjective nuance of projecting works toward a tense other than the present. The paintings are being cast like dice into places differing from the here and now.

The works ordinarily seen at museums or other sites have been thrown out into numerous times while still remaining in the present. To be sure, people’s views of paintings change, and paintings themselves age. In principle, nevertheless, paintings live for a longer time than people. Transcending time and place, we encounter subjects from the distant past in them.

Besides passage back and forth through the dimension of painting space, the title of Ishii’s solo exhibition conveys her private yearning and wishes for paintings that have withstood the temporal and spatial deformation accompanying such passage.

The word “symbol” derives from a Greek word meaning “to throw together.”*2

Use of signs in the sense that Katz ascribed to Pop Art is suited to a contemporary (time shared together) age in respect of having a provisional universality and coexisting with the consumption of the times. It may be that symbols ring out the possibilities held by signs and cast them into a different phase.

I am certain that in paintings which will be “thrown far” in Ishii’s words dwell the power of such symbols and the skill called “big technique” by Katz. Moreover, her own paintings may be moving in that direction.

Lastly, I must mention that Ishii’s works always contain a sign that is not visible to the eye: a look. Just as Doig turns boats into his own signs, Ishii makes signs out of the motifs of closed eyes and empty eyes. These eyes are also identified by the evanescence and warmth distinctive to her paintings.

The looks transformed into signs by Ishii’s hands wander around inside her paintings, in mirrors, paintings in paintings, windows, and sometimes body movements, gestures, and the lines of pastry bags. The girlish eyes (signs) are symbols throwing the existence of such gazing back at the viewer.

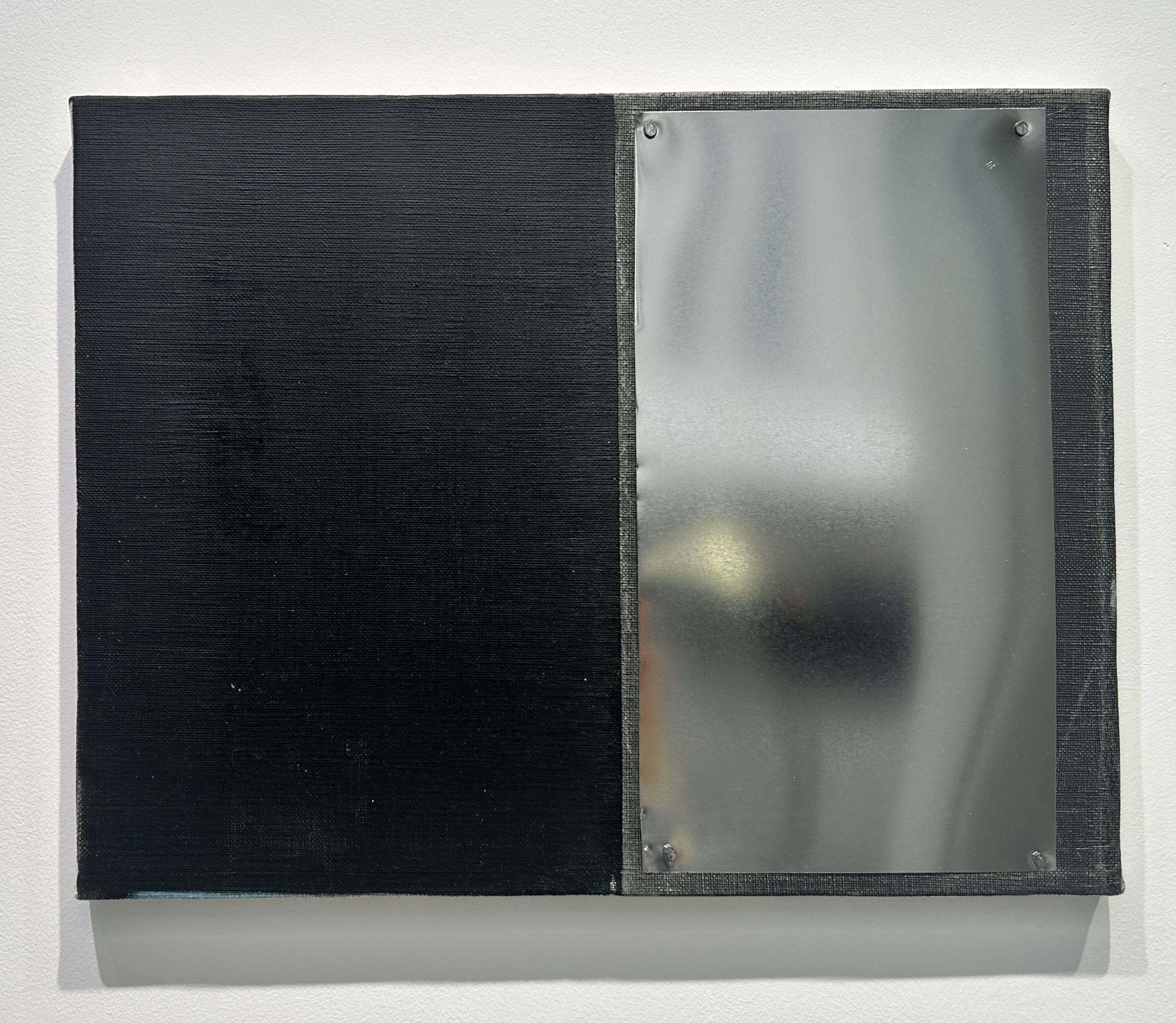

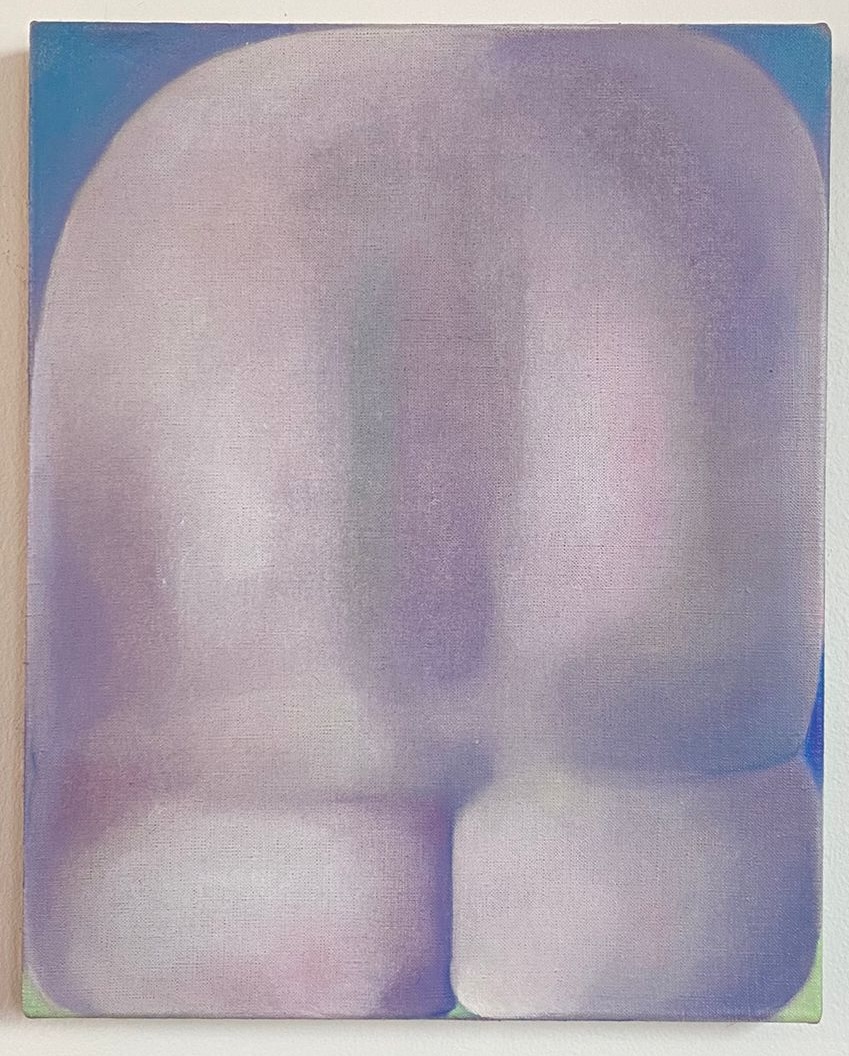

Fictional reality., a solo exhibition of works by Eri Fukami

Contrary to the impression one may initially receive from her paintings, I doubt I know of any other artist who expresses real experiences as frankly as Eri Fukami.

For example, when people say they were so surprised that they jumped into the air, they didn’t actually jump into the air. When painting such a scene, however, to depict a person jumping into the air may very well match the reality of the actual feeling that gripped the person.

Fukami attempts to make stories out of such intuitive realities, with almost no embellishment.

In her paintings, there may be several Fukamis, and her own figure may be projected on reminiscences of her grandmother. This is because such depictions match her inner feelings as “reality.”

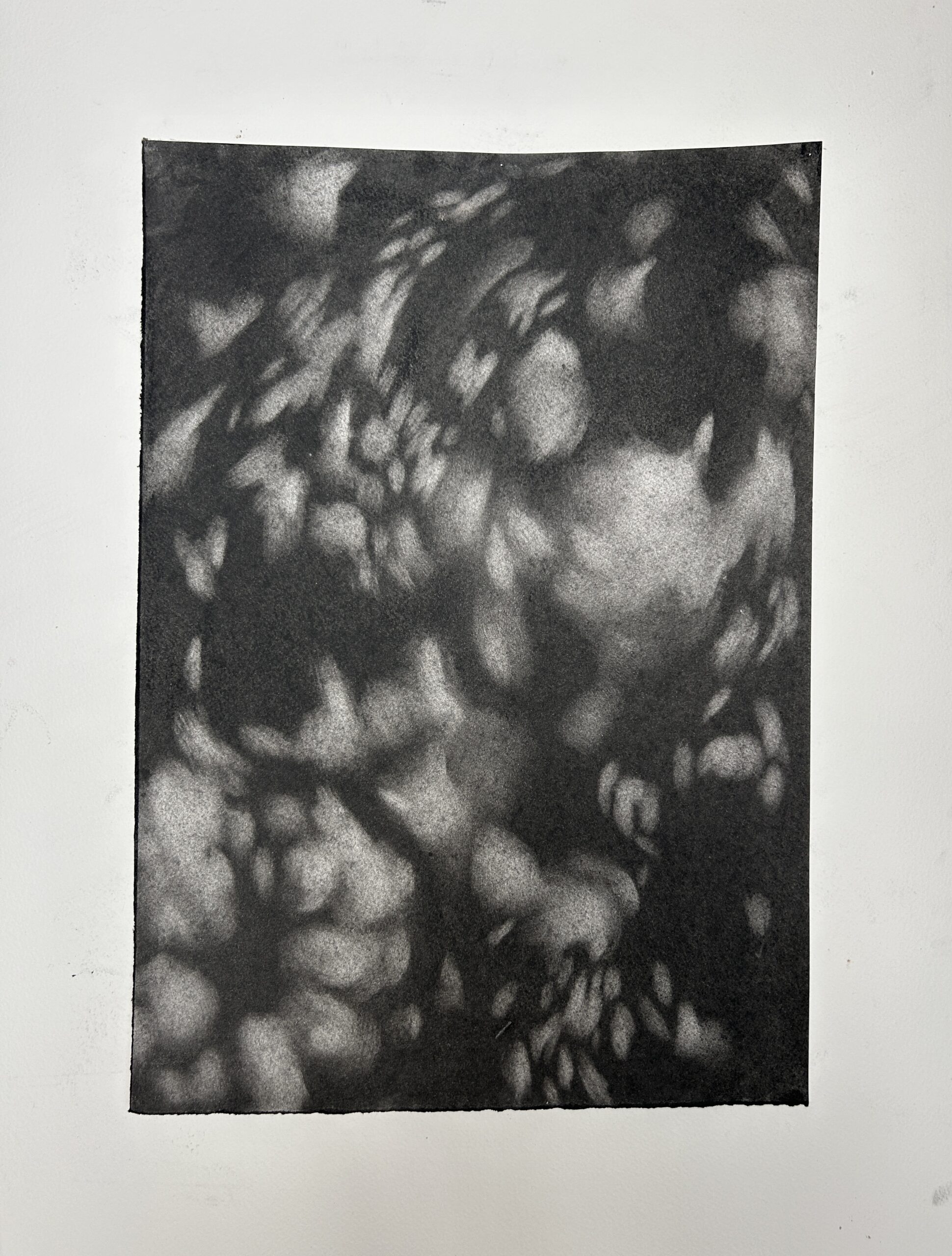

But real problems are not the whole story of Fukami’s works; many of the images appearing in them call to mind landscapes that are distant memories, dreams, and formative experiences preserved in the subconscious.

The nude figures tie mental images of Adam and Eve and other subjects related to the emergence of human beings together with intimate space represented by family and “you and I” (see Tsuioku (2022), Tsumugu seimei (2021), and Watashi hitori dake (2021)).

Gazing at the fictitious world created by Fukami in this way, we are virtually assailed by the sensation that natural images (sources of self) and primeval images (sources of the world) are connected at one place. Fukami states that to die is to return. To view life and death, and the self and others, within a cyclic process merging them into one is to participate in the outlook on the world expressed in Fukami’s paintings.

Were you and I originally one? Did we come from some single place?

Fukami’s works are a topos where this sort of awareness of the world (reality) and actual experience (reality) are encountered as a unit.

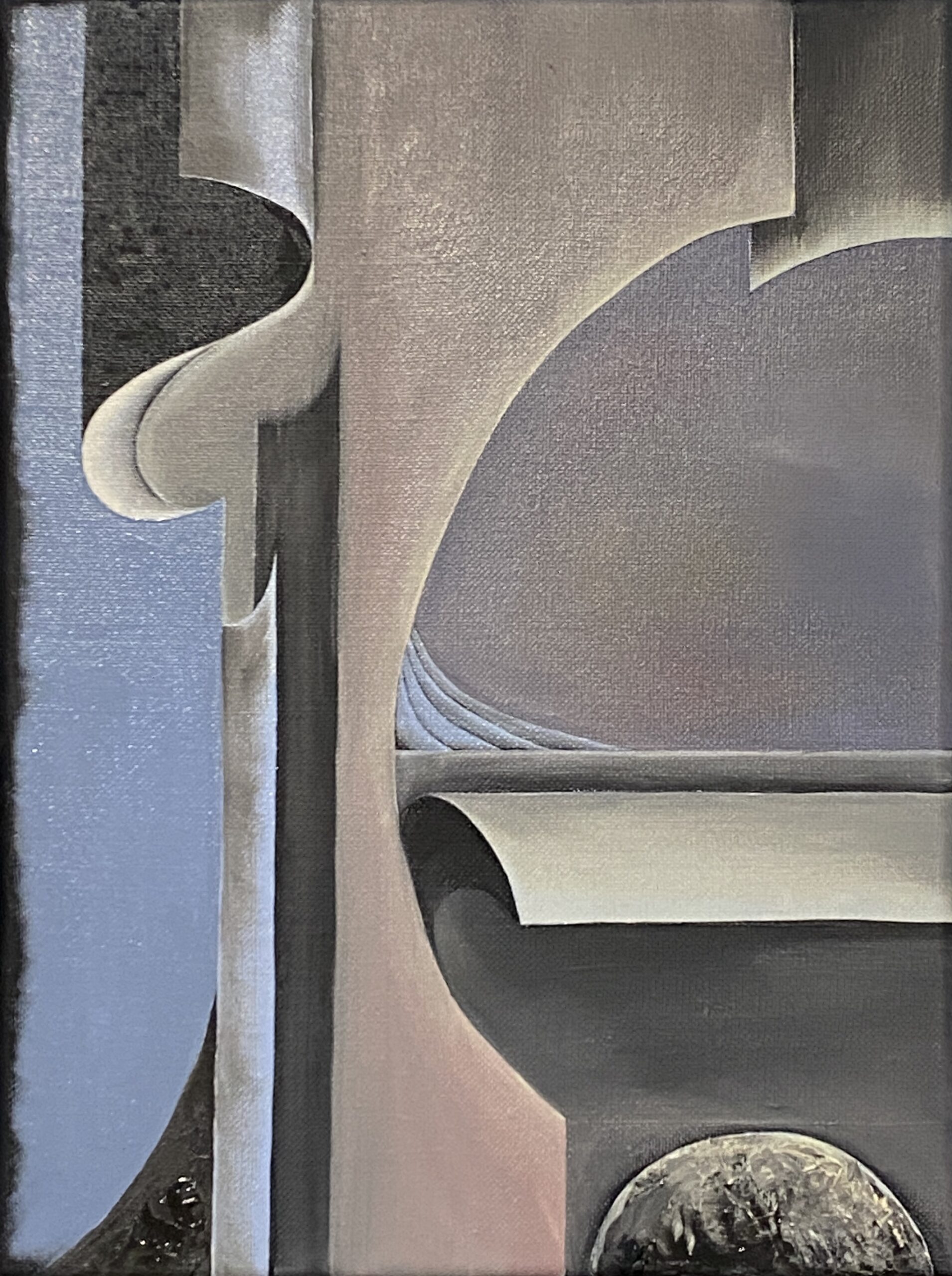

Precisely because plural times, plural places, and plural world lines dwell in a single painting as things that have been lived, Fukami’s paintings look chaotic.

To put the scene born in the brain down on the canvas in a form that is as alive as possible requires the completion of works at a speed that is as close as possible to that of synapse transmission. Fukami finished painting Tsuki ga totemo kirei na hi (2002) in about two hours.

Inevitably, the canvas manifests vivid coloration and raw brush strokes that emphasize subjectivity. The depiction of human motifs in a semiotic manner may derive less from a formalistic interest and more from a degree of resolution that facilitates the capture of bodily forms.

In respect of these expressionistic attributes, Fukami bears a certain resemblance to Shinya Azuma and Mie Iida, who belong to the same generation of artists. Azuma, however, uses representations that are more ironic and have a sham villainy, and Iida adopts a self-referential attitude toward self-referencing. They give the impression of turning back to the technique of painting after viewing the cultural framework from a meta-perspective.

In the case of Fukami’s works, the particularity about cultural regularity is not that strong. Although this is an odd way to put it, I would say she skips systemic issues and handles mythic ones.

Nevertheless, with a technique this close to sketching, Fukami’s paintings would seem to differ little from drawings. When I asked her about this, she said that there was practically no difference and that, on the contrary, drawings would have a higher degree of completion and “facilitate understanding of the linkage between her own memories and reality.” If that’s the case, why make oil paintings? Her response to this question could be summarized as follows.

“If I did drawings with crayons, which I have used since childhood and feel perfectly at home with, I could produce works with stable quality every time. With oil paintings, in contrast, the results change along with physicality. In the real world, one-time events happen every day. We have no choice but to deal with them, then and there. The same kind of thing can best be done in oil painting. Pigments are fluid, and color development and oil spread vary every time. I also change what I use in correspondence with the situation at the time. For example, I may select inorganic pigments for living beings and organic ones for dead ones. The resulting image changes accordingly.”

(From notes from an advance interview)

In this case, hard-to-handle oil pigments are likened to contact with the outer world and others. Through the medium of this otherness, a transformation is required of the self and works, like it or not.

Otherness could be regarded as a precondition for Fukami’s subjective “reality.” This is an important point. The features described so far lend the impression that Fukami is depicting “her own” inner world. But Fukami is also summoning her self from the outside.

Insofar as she is showing works in the public space of an exhibition, it goes without saying that Fukami is aware of a self incorporating the eyes of others. The narrative “reality” she spins lies in the gap of rapture open to negotiation with others.*3

In spite of this, such a subjectivistic style of painting may be expected to come in for criticism, too.

Hal Foster questions the idea of the unconscious that people who attach importance to expression of inner worlds treat as if it were their prerogative. In his view, the expressionists showcased their faults and vices, perhaps being obliviousness to how the self is culturally constructed right from the stages of inspiration and motivation. According to him, the intuitive expressions produced by these artists constitute but one of the patterns completely codified by existing art history.*4

This outlook is a criticism leveled at all artists who stress expression (or existence) alike.

As a matter of fact, Fukami’s works are at risk of making viewers think they have seen them somewhere before.

For example, to give a direct form to personal existence and emotion is something that has been done by artists of the preceding generation, e.g., Masato Kobayashi, Hiroshi Sugito, O JUN, and Reiko Ikemura. While this observation is no more than a mental association related to the ideological element, it also applies partially to the specific expression. The way trees are painted in Fukami’s A gray town that I can’t remember (2022), for example, recalls O JUN’s A dove flying away, I am surprised, and the touches of pencil, Sugito’s three roofs (2012).

Whether such similarities appear to be on the order of love or influence, or end up being inferior versions as world views, depends on the intensity of Fukami’s own works. In addition, the immediacy of painting images in their raw state unavoidably holds the danger that the works will not rise above a semiotic crudity. As I noted in the preceding text on Ishii’s art, use of signs is also linked to a flatness. As such, it would presumably be difficult to specify a technical middle ground for settlement of this issue. This boils down to simple matters, such as the cat that appears in Omoidashitara (2022) not looking like a cat at first glance, and a less than perfect conveyance of the lively swaying of flowers in the same painting. It is unclear whether the object is full expression of Fukami’s reality or a depiction that is comprehensible to the general public. But I have the feeling that Edvard Munch, Marc Chagall, and Miriam Cahn all deftly navigated these straits in their paintings.

That said, it may be that Fukami has already determined her course herself. There has been a change in the way she renders people. Her initial direction of deliberately semiotic depiction (Suki (2022)) has been followed by works that show the addition of facial expressions and accessories, a little at a time, that have enriched the portrayals.

Fukami may very well easily overcome not only my wonderings but also Foster’s line of criticism.

In this text, I have transliterated “reality” in terms of the sense of reality and perception of the world in various ways. When I asked Fukami how she would translate “reality,” she replied “chaos.” Because she was torn between that and “truth,” her reply might be completely different if I asked her again today. But “chaos” really makes a lot of sense to me.

The reality experienced by Fukami is a memory-mixed mélange of inner gut feelings and perceptions of the world. It creates a narrative world through the contact with the external world in the form of pigments and canvas.

A plural number of raw “realities” are alive on a single flat world.

It is indeed a chaos “reality.”

Symbol (…)

1.A mark or sign indicating something else. 2) An effect connecting two things that have no inherent connection (a concrete thing and an abstract thing), based on some similarity. For example, The use of a white color to express cleanliness and a black color to express sadness. (Translation of an entry from Kojien, sixth edition, edited by Izuru Shinmura, Iwanami Shoten, 2008; omission by the author)

2.Dictionary of English Etymologies*, edited by Yoshio Terazawa (Kenkyusha, first edition, 1997, p. 1393) and Greek Lexicon*, edited by Harukaze Kogawa (Daigaku Shorin, first edition, 1989, p. 198)

* Tentative translations for titles of books available only in Japanese.

3.From “Aura and Agora: On Negotiating Rapture and Speaking Between,” an essay by Homi K. Bhabha, as contained in a collection of Homi’s works in Japanese translation by Junichi Isomae and Daniel Gallimore, published by Misuzu Shobo in 2009.

4.Hal Foster, “The Expressive Fallacy,” Art in America, February 1983.

Text translated by James Koetting

1986 Born in Hokkaido

1986 Born in Hokkaido

1988 born in Colombia

1988 born in Colombia

1994 Born in Pančevo, Serbia.

1994 Born in Pančevo, Serbia.